Show All » Personal » Welcome

Thursday, June 30, 2011HUGE MONEY IN SYNTHETIC HIGHS

The Big Business of Synthetic Highs

From Bloomberg Business Week, June 20th.

Synthetic drugs that use legal compounds but mimic the highs of everything from marijuana to cocaine are proliferating among do-it-yourself pharma labs across the country. Bad trips—and fatal side effects—are increasing, too

It's a Friday afternoon in April, and Wesley Upchurch, the 24-year-old owner of Pandora Potpourri, has arrived at his factory to fill some last-minute orders for the weekend. The factory is a cramped, unmarked garage bay adjoining an auto body shop in Columbia, Mo. What Upchurch and his one full-time employee, 21-year-old Jay Harness, are making is debatable, at least in their eyes. The finished product looks like crushed grass, comes in three-gram (.11 ounce) packets, and sells for about $13 wholesale. Its key ingredient is a synthetic cannabinoid that mimics tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the active ingredient in marijuana. Upchurch, however, insists his product is incense. "There are rogue players in this industry that make the business look bad for everyone," Upchurch says. "We don't want people smoking this."

From the outside the place looks abandoned. The only sign of life is a lone security camera. Inside, two flags hang above a makeshift assembly line. One shows a coiled snake and reads "Don't Tread On Me." The other has a peace symbol. The work space consists of a long, foldout table containing a pile of lustrous, green vegetation, a pocket-calculator-size electronic scale, a stack of reflective, hot-pink Mylar foil packets, and a heat sealer. Each packet has the brand name, Bombay Breeze, and is decorated with a psychedelic logo featuring a cartoon elephant meditating among abstract-looking coils of smoke and stars.

Upchurch supervises as Harness weighs out portions of the crushed foliage, dumps it into a packet, and slides the top through the heating machine to create an airtight, tamper-proof seal. He finishes about a dozen in 10 minutes, topping off what they will need for their deliveries: two shipments of more than 1,000 packets each. Upchurch points to a disclaimer near the bottom right-hand corner of each package that reads, in all caps: "NOT FOR CONSUMPTION." Says Upchurch: "That's to discourage abuse."

His protests and disclaimers to the contrary, Pandora is getting smoked—it's being packed into bongs and reviewed on sites such as YouTube (GOOG)—for its ability to alter the mind. Like many others, Upchurch is repackaging experimental medical chemicals for mainstream store shelves, most often with some clever double-entendre in the branding. He says he sells about 41,000 packets a month, delivering directly to 50 stores around the country and shipping the rest to five other wholesalers, some of whom use Pandora's products to create their own brands. Upchurch says he ships mostly in bulk orders for larger discounts. He projects his company will earn $2.5 million in revenue with $500,000 in profits this year, depending on what federal and state laws pass. "I think my business model is based less on charts than it is on guts, or something," he says.

"Incense" such as Upchurch's, along with "bath salts" and even "toilet bowl cleaner," have been popping up at gas stations, convenience stores, "coffee shops" that don't sell much coffee, and adult novelty stores. Today, Upchurch's shipments—he uses UPS (UPS)—are headed to places called Jim's Party Cabin in Junction City, Kan., and the Venus Adult Superstore, in Texarkana, Ark. Instate, Upchurch sells to Coffee Wonk, a coffee shop in downtown Kansas City, Mo. There, 28-year-old owner Micah Riggs writes the names of his offerings in multiple colors on a dry erase board near the register. The packets themselves are kept beneath the counter. While Riggs doesn't mind his customers talking about how they will use the incense, he's as circumspect about what he is actually selling as Upchurch. Nearly everything he says is in code. He'll say things like, "Is this your first foray?" and "There are different potencies of aroma."

Customers report different reasons for trying Riggs's products. Some say they need to pass a drug test; synthetics do not show up in standard tests. Others are businessmen in khakis who like the idea of buying from someone they trust. Riggs claims to sell mostly to the military, soccer moms, teachers, and lots of firefighters. "I don't tell people what to do with it," Riggs says. "This is a marketer's dream. I underpromise and it overdelivers."

Synthetic cannabinoids are the most common of an expanding array of drugs that mimic the effects of outlawed, mostly farmed, substances but are based on manufactured and often legal compounds. In just a few years a complicated global supply chain, enabled by the Internet, has appeared to produce, package, and ship a multiplying variety of narcotics. It is taking an increasing chunk of the market for recreational drugs, estimated by Jeffrey A. Miron of Harvard and the Cato Institute to be $121 billion in North America.

Scott Collier, a diversion program manager with the Drug Enforcement Administration in St. Louis, estimates there are now at least 1,000 synthetic drugmakers in the U.S. Those are only the ones with recognizable brands. "Factor in the number of people using the Internet as a supply store and making stuff out of their basement, and that number jumps considerably," he says. Many synthetics are not complicated to make; videos detailing the process on YouTube run about ten minutes.

In the U.S., producers such as Upchurch have been making millions, if not billions. With no penalties in many states, first-time customers have been able to experiment with "incense" or "bath salts" without fear of legal consequences. There's not even an age restriction.

While untracked in the U.S. until a few years ago, the market for the kind of "incense" sold by Upchurch now generates close to $5 billion annually, according to Rick Broider, president of the North American Herbal Incense Trade Assn. (Nahita), which represents more than 650 manufacturers, wholesalers, and retailers. (Broider says his number is based on self-reported sales statistics from members.) Daniel Francis, executive director of the Retail Compliance Assn., another trade organization, founded to help inform and protect the rights of merchants, says he hired an independent analyst who came up with a similar figure.

Scrambling to control the synthetics, states are engaged in an endless game of tag. As legislators outlaw synthetic compounds, manufacturers and packagers create or find new variations, scanning medical journals for clues about lesser-known substances developed by legitimate researchers, often importing those compounds from labs in foreign countries. According to the National Conference of State Legislatures, at least 32 states have enacted legislation banning various types of synthetic cannabinoids. And another 18 have legislation pending to enact new laws or increase the penalties.

In March the DEA banned five formulas from use in commercial products. These included JWH-018, JWH-073, JWH-200, CP-47.497, and cannabicyclohexanol. JWH is named after John W. Huffman, a chemistry professor at Clemson University in South Carolina who developed it in the early 1990s. CP is code for Charles Pfizer, a precursor of Pfizer (PFE).

Synthetic marijuana first gained popularity in the European Union in 2006; at least 21 member countries reported its presence in 2009. (While the U.S. and many countries have begun to outlaw these products, at least one, New Zealand, has gone the other way. In March, government authorities announced a plan to make the sale of products with JWH-018 and -073 legal for anyone 18 and over.)

Synthetic drugs aren't just limited to aping marijuana, either. Those so-called bath salts or toilet cleaners are actually a second wave of synthetics: chemically based alternatives that simulate the effects of harder substances—some organic, some not—such as methamphetamines, cocaine, ecstasy, lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), phencyclidine (PCP), and even cocktails of all those substances mixed together. At least 38 states have also banned or have pending legislation to ban some synthetic cathinones, which mimic drugs such as methamphetamines.

Society may just be beginning to understand the implications of a developing class of drugs that deliver highs like the organic product without the hassle of farming, that can be transported in small bricks and not bales, that dogs can't or don't yet know how to smell, and that leave no trace on drug tests. There is every indication that synthetic replicas of farmed drugs, legal or not, have arrived for good. As Collier puts it, "the race is on."

Rusty Payne, a spokesman for the DEA, agrees that outlawing substances doesn't mean they will disappear. Banned blends might return to shelves or be sold underground. "A logical assumption is that the bad guys see this as a good market," he says of the synthetics. "If the way they can make the most money is smuggling drugs, there's going to be smuggling drugs."

Paul Cary, director of the Toxicology and Drug Monitoring Laboratory at University of Missouri Health Care in Columbia, Mo., works as an expert adviser for the National Association of Drug Court Professionals. While urine testing for some JWH compounds was developed in late 2010, he says it remains expensive and is available at only a handful of specialized labs around the country. "Most designer drugs are produced cheaply, extensively marketed, and quasi-legal. When the labs and laws catch up, the chemists just move on," he says. "The ability of laboratories to detect designer drugs will always lag behind these illicit chemists' ability to produce them."

Adds DEA spokesman Payne, "This stuff is not going away. We are going to be dealing with synthetic use for a long time, with new emerging chemicals coming up."

Indeed, business is in full swing at Upchurch's facility. Responding to the efforts of lawmakers, he's been changing his formulas as needed. He doesn't want the exact name of the chemicals in his recipe printed, but on that April visit his secret ingredient sits on a back shelf at his headquarters: It's a silver, kilogram-size bag of a crystalline powder containing yet another variant of a JWH-style synthetic cannabinoid.

Jeremy Morris, a senior forensic scientist with the Johnson County Sheriff's Office in Kansas, brings out his research stash—a lump of weed and an incense packet labeled Bayou Blaster (its logo is a washboard-playing alligator)—and places it on a sterile countertop alongside a microscope. It's a Wednesday afternoon in April, and he is in his crime lab, an all-white work space in Mission, Kan.

Kansas was the first state to ban synthetic cannabinoids, thanks largely to the work of Morris and his four-person team of chemists. An understated guy in a polo shirt and slacks, with a gun on his belt, Morris pulls on a pair of blue latex gloves and focuses the microscope, preparing to demonstrate the differences between traditional marijuana and the new synthetic versions. He does not buy the "incense" pitch. "It's pretty clear that people selling this product have found a legal way to be a drug dealer," he says.

The weed is obviously marijuana. It's green and brownish, with a stinky-sweet aroma. And it's hairy, covered in what are called cystolithic hairs. "Most plants do not have that kind of hair, unless it's hops," says Morris. Under a microscope the hairs look like tiny bear claws, but that doesn't matter. On the street, the physical profile is enough for police to confiscate the material and charge someone with possession.

Next, Morris pours out a sample of the incense. The vegetation is indiscernible and there is no telltale scent. "It just smells like incense," he says. And with so many potential ingredients, he notes, drug sniffing dogs are apt to be ineffective, too.

Then Morris puts the sample under a microscope, revealing a series of tiny amber beads embedded within crushed leaves. "You could mow your yard and make a product that could get you high," Morris says. "The plant is just the vehicle they put the crystals on top of." So if officers in Johnson County confiscate a suspicious packet, they have to test it. Morris must run each substance through an oven-sized machine called a gas chromatograph mass spectrometer, in which the sample is superheated. Different chemicals vaporize at different speeds. When they do, each gives off a unique fragmentation pattern, a lot like a tiny firework. The time lapsed and the explosion style provide the drug equivalent of a fingerprint.

All that testing takes time. Most police agencies have evidence backlogs of at least six months, Morris says, so it's likely some abused chemicals haven't been discovered yet. "You take one out and another just pops up," he says, shaking his head.

In late 2009 the sheriff's office began getting reports from high school resource officers about kids buying incense and smoking it. Rather than confiscate the material or try to close down the shops selling it, Morris asked undercover officers to go in and buy more. Like Upchurch when he was first setting up shop, Morris analyzed the chemicals appearing in popular brands. (Upchurch isn't a chemist; he's a former Web designer, but he paid a private chemical lab to help figure out his initial recipes.) In his own lab, Morris identified three probable ingredients in most blends—JWH-018, JWH-073, and HU-210—and proposed that Kansas ban them. In March 2010 the state made all three illegal. Other states followed suit. Louisiana has even banned the use of the plant damiana, a central American shrub that smells like chamomile and looks a little like pot. The current DEA ban covers five cannabinoids as well as any "analogues," small manipulations of molecular structures that essentially work the same as the original molecule.

Upchurch orders many of his "special additives" from China, and both he and Morris use the international export directory Alibaba.com to see what's available. Search "buy JWH" and you'll find at least 3,800 Chinese labs standing by for custom orders. Hubei Prosperity Galaxy Chemical, for example, offers photos of its operation in Hubei on mainland China, with rows of workers in white suits. Hubei notes on its website that it can ship 5,000 kilograms of JWH-019 per month. (The company declined to comment.) One hundred kilograms is enough to make the equivalent of about 1 million joints of marijuana. Such Web traffic appears to be completely unregulated. On a recent day, Morris spotted one site that had mislabeled an ultrastrong hallucinogen as a low-dose cannabinoid.

For incense smokers, product mislabeling and reformulation can be dangerous. "All of these things act on various parts of your brain called receptor sites," Morris says, describing the biochemistry that helps regulate normal states of consciousness. Synthetic cannabinoids target the CB1 and CB2 receptors, which either cause hallucinations in the first instance or can alleviate nausea and instill calm in the second. "Think of it as a lock-and-key system," he says. "The receptor site is the lock and the drug is the key. As the key goes into the lock, it sort of opens up the psychoactive properties of the receptor site."

After testing more than 100 packets from different suppliers, Morris has noticed a disturbing trend: There is no trend. The type and quantity of mind-altering agents in many blends can vary not only between brands but also between packets of the same stuff. He's found processors using different synthetic cannabinoids anywhere from two to more than 500 times stronger than THC. Some target the CB1, others the CB2. Many manufacturers are mixing multiple chemicals together to create signature blends, forging new combinations.

Side effects and tragedies have risen along with profits. The American Association of Poison Control Centers logged just 14 calls about the harmful effects of incense in 2009. That number jumped to 2,874 in 2010. By the end of May 2011, it had fielded an additional 2,324, on pace to double last year's numbers. Hospitals have reported that smoking incense can cause agitation, racing heartbeat, vomiting, intense hallucinations, and seizures. "Marijuana can make you calm and relaxed, but this seems to cause anxiety," says Dr. Anthony J. Scalzo, medical director of Missouri Poison Control, who spotted the first outbreak of emergency room visits in late 2009. "People think that if you can buy it legally, it must be safe. But they don't know what they are dealing with," he says.

According to news reports, in Indianola, Iowa, a recent high school grad smoked some incense that was bought at a Des Moines mall and told friends "that he felt like he was in hell." Ninety minutes later he came home, took a family rifle, and killed himself. In Omaha a student stormed his high school in January and shot and killed the assistant principal and himself. Toxicology reports later indicated the presence of synthetic cannabinoids in his system.

Many cathinones are repackaged as "bath salts"—those tiny, soluble gel capsules often sold in large bottles at such places as Bath & Body Works. Instead of being sold by the jar, though, they are sold at much smaller retailers in small packets with names such as Sexperience, Ivory Wave, or Vanilla Sky for up to $50 a pop. Rather than drop one in the bath water, users crush it up to be snorted, smoked, or swallowed. Bath salt usage has followed a similar spike: There were 302 calls to poison centers in 2010 and 2,507 by the end of May this year. According to Dr. Mark Ryan, director of the Louisiana Poison Center, these bath salts can cause paranoia, extreme anxiety, delusion, combativeness, suicidal thoughts, chest pains, and even "excited delirium," the so-called Superman effect, where a user becomes so excited and detached from reality that he or she continues to rampage even after being shot, becoming nearly impossible to restrain. Additional news reports show that in Louisiana a 21-year-old allegedly snorted a pack of bath salts and suffered three days of intermittent psychotic episodes before fatally shooting himself. Other cases of users losing control include a Mississippi man who used a skinning knife to slash his own face, a Kentucky woman who abandoned her two-year-old son along the interstate after hallucinating that he was a demon, and a West Virginia man who dressed up in a bra and panties and stabbed his neighbor's pygmy goat to death.

Initially the DEA pinpointed Spice and K2 (K2, the mountain, is really high) as the two main brands of incense being abused. Spice was European; in 2009, U.S. Customs and Border Protection banned its import. K2 was domestic, originally made by Jonathan Clark Sloan, who runs Bouncing Bear Botanicals, an exotic plant and natural extracts dealer operating out of a warehouse in Oskaloosa, Kan.

As two of the more popular brands, the names K2 and Spice have become synonymous with herbal incense mixed with cannibinoids. "It's like when you say Xerox (XRX) but you mean copying," says the DEA's Collier. "The name has taken on a life of its own."

Authorities have come down on Sloan, but not for K2. On Feb.4, 2010, the Kansas Bureau of Investigation and sheriff's officers from Jefferson and nearby Johnson counties joined with U.S. Food and Drug Administration officials to raid the premises of Bouncing Bear. Sloan was charged in state court with 20 counts, including unlawful cultivation and distribution of several controlled substances—stimulants such as mescaline, bufotenine, dimethyltryptamine, and lysergic acid amide, which were allegedly being harvested from a series of cactus plants, river toads, tree barks, and Hawaiian baby wood rose seeds, respectively. An FDA spokesperson refused to comment on whether an investigation is ongoing. Sloan has yet to plead.

Sloan's preliminary hearing is set for mid-September. No state or federal charges regarding the manufacturing and distribution of K2 specifically have been filed. "That was certainly an issue at the time, but not an overriding issue. There were a lot of overriding drugs involved," says Jefferson County attorney Robert Fox, who is in charge of prosecuting the case.

For now, Sloan has ceased making K2, though he remains committed to the business and the idea of selling a brand as much as a product. "We licensed the K2 name to another company," he writes in an e-mail to Bloomberg Businessweek. He's also suing two competitors for copyright infringement to protect his trade name. There may be some sense in Sloan's approach, since the crackdown on his operation hasn't hurt demand for synthetic drugs and has only raised the profile of the name. The name K2 could even work for a new, legal blend.

To an extent, incense manufacturers are trying to legitimize their nascent industry. Broider, of the herbal incense trade group, says Nahita has asked its manufacturing members to voluntarily publish their contact information and to assign numbers to their products so any bad batches can be reported and recalled. He is against formal regulation. "It's not the taxpayers' burden to regulate a private market," he says.

In May the Retail Compliance Assn. went further, petitioning congressional representatives to consider a federal licensing system to help track both the number of manufacturers and distributors operating and the chemicals and dosages they are using. Unlike Upchurch, RCA states openly that the products are likely to be consumed. "There is no doubt that people are buying these products and using them off-label. They are going to do with it what they want to do with it," RCA director Francis says. The RCA's official position is not to sell to anyone under 21. It also has suggested enacting a special product tax, much like that applied to cigarettes, to help address potential health problems related to use of the products. "There's got to be a resource for responding to any claims of addiction or ill consumers," he says.

Upchurch belongs to both trade groups and has adopted his own restrictions. The back of each packet bears two more disclaimers: One clearly states that none of the federally banned substances are in his packets. The other states that the packets are not for sale to anyone under 19 years old. He also says he tests his products twice during manufacturing to ensure quality. First, every shipment of raw base chemicals that arrives is sent off to a DEA-registered testing lab to confirm it matches what was ordered. Second, each final batch of product is also sent to a lab to make sure it was blended properly and not contaminated by ingredients from other blends. His ratio of cannabinoids to vegetation needs to remain constant. The target ratio among mixed cannabinoids must remain consistent, too; anything with more than a 5percent variation is thrown out. "We don't want it to be a drug. If we put in something that is extremely potent, it will be abused," he says.

Attention to production and labeling doesn't seem to reassure law enforcement. This spring, Morris came up with a new approach to combating the drugs. Rather than ferret out problem ingredients one by one, he successfully petitioned the Kansas legislature to ban the seven chemical classes most associated with cannabinoids. When the law went into effect at the end of March, it banned hundreds of compounds at once. Eight other states, including Missouri, have adopted similar measures. Kansas and four other states have also applied the tactic to bath salts, banning a wide class of cathinones that include popular stimulants such as mephedrone and methylenedioxypyrovalerone. Such approaches could become a template for broader national action: Congress is considering a class-based synthetic cannabinoid ban. It would also apply to the next generation of product lines, such as capsule-based synthetic cannabinoid "plant fertilizers," supposedly for house plants.

The Missouri law banning synthetic cannabinoids entirely will take effect in August. For Pandora Potpourri, that means going back to the lab. On a Friday in early May, Upchurch and Harness don black rubber gloves and respirators, then congregate in the rear of the garage to brew up a new batch of test product. It's not a cannabinoid but a lab-made enzyme inhibitor with anti-depressant and anti-anxiety effects, Upchurch says. In the work zone are two mixers, a large scale, and a cooling rack stacked with cookie sheets. The top three slots are already filled with one-kilo trays of a multicolored potpourri spread thin to help it dry quickly and evenly.

"Those are keys from this morning," Harness tells Upchurch. Upchurch looks skeptical. "Keys? Are we calling them 'keys' now? I think you mean kilograms," he says. They weigh out more than 1,000 grams of damiana and mullein, a yellow-flowered Mediterranean shrub. Next, Harness opens a large glass jar filled with white powder, pouring what appears to be a few tablespoons' worth into a large plastic measuring jug situated on the scale. To dissolve the powder he adds a bottle of the grain alcohol Everclear, their latest mixing solvent. Harness stirs the concoction with a paint stick until it looks like a clumpy vanilla milkshake, then pops open another jug to add more grain alcohol.

Upchurch isn't happy. "They all dissolve differently," he says to himself. Usually he can dilute 250 grams of cannabinoid per gallon, meaning it would take about one bottle of booze to merge with the host plant. Eventually he and Harness turn on both mixing bowls. Upchurch needs this test to succeed. So far he's invested $40,000 buying and researching new chemicals, but none have worked quite right. For a small-time business, that's an expensive learning curve. "If someone is creating a law on something that we have research on, the next logical step is we have to create something new, where less is known about it," he says.

Law enforcement has affected business in another way, too. Behind Upchurch there is a shelf lined with large, open boxes filled with different kinds of vegetation. Because state laws aren't the same and can change so quickly, he's switched from creating large custom batches for each region to creating premixes of treated ingredients to meet the standards of various states. "When compounds become outlawed, we remove them and replace them with suitable alternatives," he says. "In general that may still vary from lot to lot based on destination."

Even so, business is good—so good that Upchurch just bought a new bag sealer that can print the company name on each seal to foil counterfeiters. He has four regional salesmen and is looking to expand, though he says he doesn't ask too much about his troop's sales pitches.

After pouring his mixes onto some cookie sheets and setting them out to dry, he mentions that he's also going back to school, this time for an online master's degree in international business and marketing.

If Upchurch doesn't find the next synthetic, someone else will. Micah Riggs, for one, may have been trying. In late September 2010, police reported having discovered a lab above Coffee Wonk. According to the probable-cause statement, there was a recently graduated chemist from the University of Kansas working there who admitted attempting to synthesize new strains of JWH. Riggs has been charged with intent to create a controlled substance or a controlled substance analogue. In May he was arraigned and pled not guilty. His trial is set for December. Riggs points out that he formed a company, Wonk Labs LLC, purchased most of his supplies from a mainstream research supply company, and was already looking for more formal office space. "We weren't planning to make any set compound, we were in the research phase," he says. "Things like this scare creative people from ever going into business."

Paynter is a Bloomberg Businessweek contributor.

Top

Show All » Personal » Welcome

Wednesday, May 18, 2011DEA, Bath Salts, New Formula Spice

Bath Salts and New K2/Spice

Many companies are

already testing for synthetics (formula tweakers) as well as for the original

categories of drugs found in the Five Panel. The reason is simple. The new synthetics are

easily available and relatively inexpensive.

DEA

Currently, the DEA is

researching Bath Salts with a mention of gathering the information necessary to

make them Schedule 1.

Contact Us. Cassandra Prioleau, Ph.D.

Drug Science Specialist, U.S. Drug

Enforcement Administration (DEA)

DEA Headquarters/ Phone - 202.307.7294, Fax 202.353-1263

Email – cassandra.prioleau@usdoj.gov

If you are not up-to-date on

available synthetics, the following could be of interest.

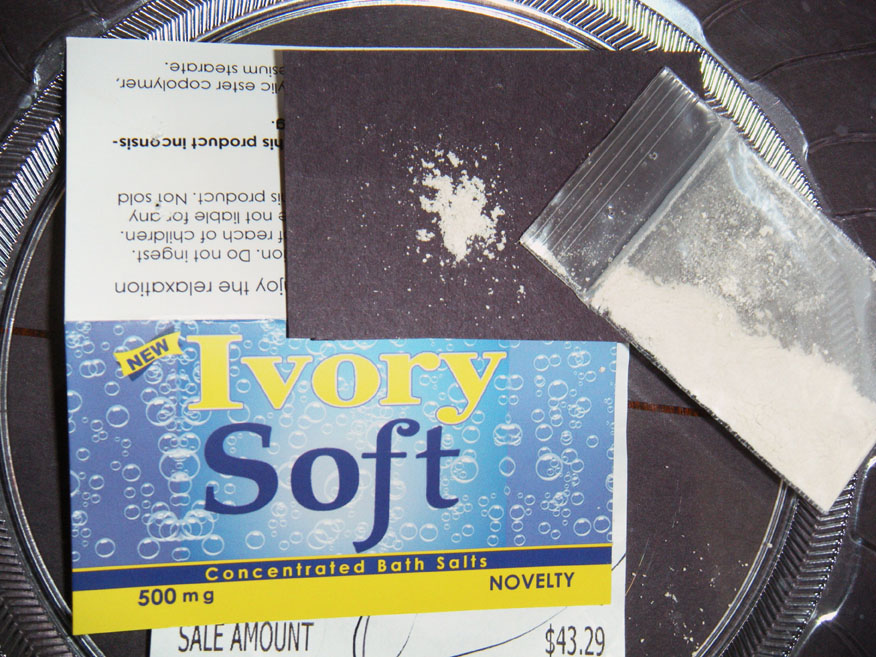

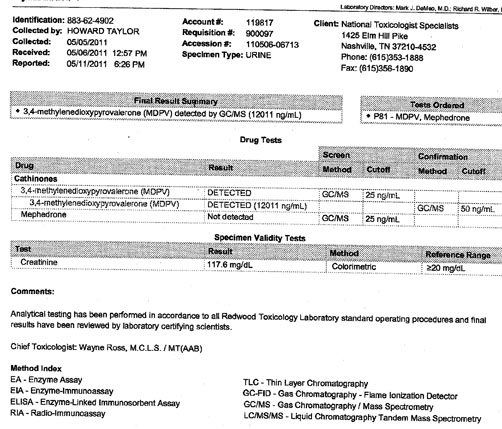

Scenario: These Bath Salts were purchased within the

last two weeks from a curb market in Nashville, TN, and forwarded to a

laboratory that tests these types of products.

This sample was tested and contained MDPV (Methylenedioxyprronvlerone), a psychoactive drug with stimulant properties which acts as a norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitor. It is sold under the names Ivory Soft, Blue Silk, Euphoria, Hurricane Charlie and is often referred to in the media as "copy-cat coke" and "the devil". If you look closely at the bottom of the picture above, you will see the purchase price of $43.29 on the receipt for 500 m.g.

-0-

Top

Show All » Personal » Welcome

Wednesday, April 13, 2011Heroin: NOT EVEN ONCE!

HEROIN, A St. Louis Area Eidemic!

This heroin addict just transformed herself from a pleasant-looking woman into someone barely recognizable. Such is the effect of drugs like heroin on its abusers.

BEFORE AFTER

Heroin Use Growing, Addicting, and Killing

In St. Louis County, police Chief Tim Fitch says: “dealers are snaring kids with a stronger version of heroin because they can be smoked, snorted or injected just under the skin (Skin Popping). Since the drug is so potent that it does not have to be injected to cause the ‘high’, or perhaps more precisely, the ‘low’- heroin is a central nervous system depressant - many have been fooled into believing it is now just a recreational drug".

Many first timers’ don’t understand how ‘good’ the junk is, (as high as 90% pure), the chance of OD’ing is greater than ever.

Powered herioin (most likely Mexican Brown as below.)

Last week, a special agent for the DEA told the St. Louis Post Dispatch that heroin overdose deaths have doubled in the St. Louis area in the last few years, and one of the reasons is the fact that the drug is now available to teens for about $10 for a two-hour high.

Mexican Brown China White

various other websites.

The Faces of Addiction attest to the power of the drug.

-0-

Top

Show All » Personal » Welcome

Monday, April 11, 2011Synthetic Coke or another Amp? You decide!

Synthetic Coke or another Amp? You decide!

April, 2011

NASHVILLE, Tenn. – Items like Cloud 9 Bath Salts and Molly's Plant Food are cheap and readily available at local convenience stores and now people are using such substances to get high.

The products are made with a synthetic form of cocaine and perfectly legal, according to John Benitez, Managing Director for the Tennessee Poison Center.

He told Nashville's News 2 when the white powder is smoked, snorted, ingested or injected, it gives the same euphoric high you'd feel when using cocaine.

"Typically, it's like an amphetamine, like drug amphetamines in general because you to have hallucinations, [you're] feeling good, being very awake, alert," he explained.

At one local convenience store, the clerk told Nashville News Molly's Plant Food is an energy pill people are taking advantage of. "I would never ever try this," an employee told Nashville News off camera. "I heard it's making people sick, I mean it says plant food. I don't understand."

Side effects of synthetic cocaine include increased heart rate, nosebleeds, hallucinations, seizures and kidney failure. Looking closely at the chemical make-up, Doctor Benitz said it's nearly identical to the amphetamine found in cocaine. Several states are taking action including Kentucky, Florida, Louisiana,Hawaii,igan and North Dakota.

BATH SALTS or Synthetic Cocaine?

The fake coke was just as easy to find online at both Amazon.com in the form of Cloud 9 Bath Salts and GoFaded.com in Molly's Plant Food.

Information for this posting came from WKRN, News 2, The Nashville Tennessean, Superior Training Solutions, and several other photo sites.

Top

Show All » Personal » Welcome

Wednesday, March 2, 2011Florida Pill Mills raid nets $2.2m & 70 cars

Operation Pill Nation nets 70 cars and $2.2 million cash.

Oxycodone/Psychotherapeutics: This week- DEA Agents arrested 22 people, garbed over $2.2 million, and 70 vehicles, including numerous exotic cars. These arrests are the first and result from 340 undercover buys of prescription drugs from over 60 doctors in more than 40 “pill mills” in South Florida.

Areas in the U.S. where Oxycodone is most abused.

Among those arrested were doctors who were conspiring to distribute and dispense more than 660,000 dosage units of the Schedule II narcotic oxycodone. The DEA considers prescription drug abuse as this country’s fastest growing drug problem and pill mills are fueling much of that growth.

The indictment alleges that the defendants marketed the clinics through more than 1,600 internet sites, required immediate cash payments from patients for a clinic “visit fee,” and falsified patients’ urine tests for a fee to justify the highly addictive pain medications.

Currently, drug dealers can sell a 30 mg oxycodone pill on the street for $10 to $30. The drug can be crushed and snorted or dissolved and injected to get an immediate high.

Top

Show All » Personal » Welcome

Wednesday, March 2, 2011Is it everywhere? Fake Coke easy purchase

Use of 'fake cocaine’ is

gaining popularity; U.S. issues alert

Sold as ‘bath salts,' using the powders are viewed as perilous. In their search for new and legal ways to get high, people are increasingly ingesting an addictive substance sold in stores as bath salts, say police and health officials in Missouri, Florida, Illinois and Louisiana.

Also called Molly's Plant food

The ‘bath salts’ are sold in 50-milligram Packets for $25 to $50 each.

Packages of some of the bath salts or crystals are labeled Cloud 9, White Dove, Blue Silk, Pure Ivory, Snow Leopard, Lunar Wave, as well as White Night, Bliss, and Vanilla Sky.

Recently the side effects included two suicides in Louisiana, dozens of emergency room visits to Florida hospitals and a third suicide in St Joseph, MO.

As of yet, the drug(s) are not specifically banned although several states are moving to do so. The DEA is reportedly also looking at the situation seriously as many of the stores that are selling the synthetic tweakers are the very same that were selling K2/Spice (synthetic THC). The DEA used its emergency authority to ban the five K2 chemicals on March 1, 2011.

-0-

Top

Show All » Personal » Welcome

Thursday, February 3, 2011Marijuana Soda

Marijuana Soda

Marijuana Soda

Feb 1, 2011 by Community Manager Olivia | Categories Drugs, Marijuana, Teenagers, Tweens, underage drinking

It’s designer, Clay Butler, says the soda pot line — called Canna Cola — will include “flagship cola drink Canna Cola, the Dr Pepper–like Doc Weed, the lemon-lime Sour Diesel, the grape-flavored Grape Ape and the orange-flavored Orange Kush,” according to the Santa Crux Sentinel.

The soda will contain 35 to 65 milligrams of THC (tetrahydrocannabinol), the main psychoactive ingredient in cannabis. The labels promise “12 mind blowing ounces.”

Canna Cola’s makers plan to sell it to medical-marijuana dispensaries in Colorado, and hope to launch it in California by the spring.

Looming, however, is a bill in Congress sponsored by Sen. Dianne Feinstein, the so-called “Brownie Law,” which passed the Senate last year. It would increase penalties for makers of products that combine marijuana with “a candy product” or anyone who markets such products to minors.

Find out more about marijuana soda in Bud in a Bottle: New Marijuana Soda to Launch in Feb.

Top

Show All » Personal » Welcome

Monday, January 10, 2011K2-Spice & More Synthetics

IMPORTANT. This white paper is not an attempt to create a scholarly or detailed article but rather just a compilation that provides basic information to lay people who are employed in the drug free workplace testing profession. The information has been gathered over the last six months from internet research and personal conversations. The complete list of resources is provided at the end of the article. Any inaccuracies are the sole responsibility of this writer. Mac / J. Mac Allen

[Editor’s Note: The first paragraph on each topic presents a summary of the information. Where appropriate, additional information is offered in Expanded Paragraphs.]

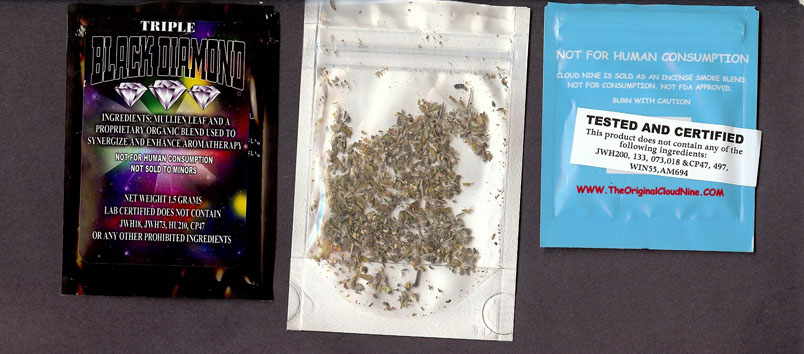

Both K2 and Spice are generic terms used currently to refer to any “carrier” sprayed with a synthetic cannabis drug product. When inhaled or ingested, these synthetic compounds are described by users as having many of the same effects as THC - the cannabinoid in marijuana. These products have been marketed as incense and stamped as NOT FOR HUMAN CONSUMPTION. However, there is no doubt that many who purchase K2/Spice intend to inhale its fumes and get ‘high’. The compound that has most frequently been used to activate the cannabinoid receptors when inhaling K2/Spice has the chemical designation JWH-018. JWH-018 is normally created in liquid form and then sprayed on whatever substances the manufacturer likes – usually crushed herbs and flowers. The only requirement for the underlying carrier is that it can burn and release the smoke made from the drug.

Please note the small pieces of herb, flowers and combustible materials visible through the K2/Spice packages. Those materials are sprayed with a synthetic cannabinoid, allowed to dry, and then packaged in these small containers – approximately 3”x3”- that have zip locks across the top of the envelope.

The actual name K2 was taken from the surveyor’s mark for the second highest peak on the planet, referred to by many as the Savage Mountain. For every four people who have reached the summit, one has died trying. It is second highest to Mr. Everest and is located on the border between Pakistan/Kashmir and

Expanded - What is the Drug Called K2/Spice?

K2/Spice is generally a mixture of burnable “carrier” ingredients that have been sprayed with the chemical compound JWH-018, although 018 is not the only synthetic cannabinoid that has been found in K2/Spice. An analysis of samples took place after the German prohibition of JWH-018 and it was found that the newer versions of K2/Spice had been sold with JWH-073 rather than 018 as the active ingredient. This was simply another way to skirt the law. Another potent synthetic cannabinoid, HU-210, first synthesized in the late 1980s at the Hebrew University (hence the HU designation), and now classified as a research drug, has also been reportedly found in K2/Spice seized by U.S. Customs and Border Protection. Like THC, which is the active ingredient in marijuana, these synthetic cannabinoids switch on the cannabinoid receptors found on many cells in the brain/body. The brain is particularly rich in the CB1 cannabinoid receptors. But most synthetic cannabinoids are quite different from the chemical structure of THC. And unlike cannabis, the new drugs have never been tested in humans.

2. Who Invented JWH-018?

JWH-018 was first created in 1995 in the lab of John W. Huffman, Ph.D., a Research Chemist and professor working on the organic receptors in the body/mind at Clemson University in South Carolina. The project was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). The intent was to make chemicals which imitated the actions of THC in the brain that could be used as both ‘carriers’ and medicines. During the project, one of Dr. Huffman’s assistants formulated what has become the most common ingredient in K2/Spice, the compound named JWH-018. JWH-018, named after Dr. Huffman (JWH), was given the 18 designation because it was the 18th such compound his lab team made during the research project.

Expanded - Who Invented JWH-018?

Dr. Huffman earned his B.S. (1954) from Northwestern University followed by his M.A. and Ph.D (1957) with the late Prof. R.B. Woodward at Harvard. He began his academic career at the Georgia Institute of Technology (1957-1960) and joined Clemson as assistant professor in 1960. He was a Pre-Doctoral Fellow at Harvard and received an NIH Career Development Award (1965-1970). He was a visiting professor at

Interviewed several times in the press, when asked why he thought manufacturers decided to use JWH-018 rather than any of the other compounds his team invented*, Dr Huffman theorized “that the compound was chosen because it was the easiest of the many chemicals that came out of that project to synthesize outside a lab.” Huffman went on to say that JWH-018 “requires just two steps using commercial products, and can be more potent than THC.”

*Huffman interviews indicate there were several hundred more compounds that were produced during the research. They included JWH-073, JWH-200, JWH-250 and other numbered compounds that seem to end at JWH-382. Another such substance, not invented by Huffman, was named cannabicyclohexanol. It was originally a Pfizer compound first synthesized in 1979.

The primary target of the Huffman research was to develop chemicals that mimicked marijuana or cannabimimetics in the brain, i.e., produce synthetic analogues and metabolites of delta-9 tetrahydrocannabinol/THC that could result in new medicines. In other words, Huffman and his team did not set out to create the active ingredient in K2/Spice or any other illegal drug. The long-term goals of the research were two-fold and included the potential development of a new pharmaceutical product that targeted the endocannabinoid receptors in the body and exploration of the geometry of both the cannabinoid brain receptors, CB1, and peripheral CB2 THC receptors. Indeed, the THC analogues that were created reportedly showed promise for the treatment of nausea, glaucoma, as appetite stimulants, and as an aid in the research of multiple sclerosis and AIDS. Over the course of twenty years, Huffman and his team of researchers developed approximately 450 synthetic cannabinoid compounds. 018 was just one such compound/bi-product of the research

Expanded - Why Was JWH-018/K2/Spice Invented?

Besides the reasons above, before the 1980s, it was often speculated that cannabinoids produced their physiological and behavioral effects (make the user ‘high), via NON SPECIFIC cell membranes, instead of interacting with specific membrane-bound receptors. The Huffman research helped to resolve that debate. Receptors for cannabinoids are specific, are commonly found in animals, and have been found in mammals, birds, fish, and reptiles.

Present medicinal uses of compounds that interact with this system include analgesia, suppression of chemotherapy-induced nausea, appetite stimulant for illness and medication-related weight loss, reducing motor symptoms (e.g., spasticity, ataxia, weakness) in multiple sclerosis, and reduction of intraocular pressure in glaucoma.

Synthetic cannabis products sold under the brand name Spice seemed to have first appeared in Europe in 2002. By 2004 they were firmly entrenched in

Expanded - Where Was K2/Spice First Sold?

In 2006 the brand name Spice gained general popularity in England and remained the dominant brand until 2008 when competing brands started to appear. These were also dubbed Spice. The product was supposed to be a way to get high legally on what was said to be a mixture of herbs and flowers. The name has now come to be used for both the brand 'Spice' and for all herbal blends with synthetic cannabinoids added. In 2009, The European Monitoring Center for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) reported that ‘Spice’ products were identified in 21 of the 30 participating countries. However, when tested, it was found that the herbs listed on the packaging, when analyzed by a laboratory in Germany, were often not found in the product at all. Herbs listed on the packaging of Spice included Canavalia maritima, Nymphaea caerulea, Scutellaria nana, Pedicularis densiflora, Leonotis leonurus, Zornia latifolia, Nelumbo nucifera and Leonurus sibiricus. After testing by the German lab, it was announced that some Spice products contained an undisclosed analogue of the synthetic cannabinoid CP 47,497, and JWH-018. CP 47,497, along with its dimethylhexyl and dimethyl-non-1 homologues were the analogue that had been named cannbicyclohexanol. Yet another potent synthetic cannabinoid, HU-210, was reported to be found in Spice found seized by U.S. Customs and Border Protection. By then many manufacturers, attempting to get around the ban, had dropped JWH-018 for JWH-73.

As with any non controlled street drug, different ratios of different synthetics have been found in different Spice brands with cannabinoid content varying from 0.2% to 3%. In short, much like the current state of Ecstasy, it is almost impossible to know how much of what a user is ingesting. As put by yet another medical expert, when you take these drugs, you are hijacking the part of the brain important for many functions: temperature control, food intake, perception, memory, and problem solving. Huffman, himself, is quoted as saying “anyone who smokes this stuff is stupid.”

Narcotics experts say many of these novel drugs are manufactured in China, where lax regulations makes it easy for companies to produce and export a cornucopia of chemicals. For instance, Les Iversen, chairman of the U.K.'s Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs, which advises the governments of the United Kingdom on new substances, relayed that customs officials at Heathrow Airport recently seized a large shipment of white powder from China that was labeled "glucose" but contained mephedrone, an analogue or “Tweaker” of an amphetamine formula.

China also supplies raw ingredients to manufacturers located elsewhere although Chinese officials now say the country is taking steps to control the flow of new drugs. On September 1, 2010 China began regulating mephedrone as a "category I psychotropic substance." That means anyone importing or exporting it needs a special license. In a written statement, China's State Food and Drug Administration said it has "strengthened monitoring of the situation in the country," and is ready to work with other countries to "exchange information, share resources and jointly respond to new emerging problems of drug abuse."

U.S. Armed Services: Following cases in Japan involving the use of synthetic cannabis by Navy and Marine Corps personnel, a ban was issued as of January 4, 2010. On

David Llewellyn is part of a wave of chemically savvy entrepreneurs who see gold in the gray zone between legal and illegal drugs. Quite simply he and his chemists make analogues or “tweak” known chemical formula to create new drugs. Mr. Llewellyn says he buys his raw ingredients online from Chinese suppliers, who charge rock-bottom prices and who, to date, have asked few questions about his business. The powders and liquids arrive by plane in 1-kilogram sacks and 25-liter drums and go to a warehouse in

But the 49-year-old Scotsman is NOT in the illegal drug trade. Instead, when his construction business failed a few years ago he entered the so-called "legal high" business—a burgeoning industry producing new psychoactive powders and pills that are marketed as "not for human consumption." Mr. Llewellyn, a self-described former addict, started out making a “tweaker” named mephedrone (mentioned prior and somewhat like the stimulant Ecstasy-a methamphetamine). The tweaker was known as Meow Meow and was very popular with the European clubbing set. Once governments began banning it earlier last year Mr. Llewellyn, and a chemistry-savvy partner, started selling something they dubbed Nopaine—a stimulant they concocted by tweaking the molecular structure of the attention-deficit drug Ritalin.

Nopaine "is every bit as good as cocaine," says Mr. Llewellyn, who has lived in

If the proponents of legalized marijuana have their way, the answer will be no. At this moment it seems the public will continue to see both synthetic and organic, in various legal and illegal configurations.

ORGANIC, A first: A conference on marijuana billed as A Forum for Discussion of Business, Legal & Health Issues was held at the Hilton, New York City last October 25th and 26th. Those in attendance included Ms. Trish Regan, a CNBC anchor, who moderated the panel discussion entitled “Entrepreneurial Visions: The Business of Marijuana. Ms. Regan was also featured in the CNBC documentary, “Marijuana Inc.: Inside America’s Pot Industry. According to the agenda and press reports, the conference also featured some well established panelists as well as the following who were listed as featured speakers:

Daid E. Smith, MD, Addiction Medicine, Newport Academy, Founder, Haight Ashbury Free Medical Clinic

Jeffery A. Miron: Director of Undergraduate Studies, Department of Economics, Harvard University

SYNTHETICS: In 2009, 24 new "psychoactive substances" were identified in Europe, almost double the number reported in 2008, that according to the Lisbon-based European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. (EMCDDA). A few included:

Mephedrone. Also known as Meow Meow, Drone and M-Cat, this drug is similar to methamphetamine (speed). Police reports say it has been responsible for at least three deaths in Europe. It has recently been banned in most European countries.

Naphyrone. Also known as NRG-1. Similar to amphetamines. Banned last year in the U.K.

MDAI. Similar to MDMA, or ecstasy/X. Still legal in many countries.

BZP. Belongs to a class of drugs called piperazines, which mimic the effects of MDMA. Piperazines are used in industry to make plastics, resins, pesticides and brake fluid. BZP was once investigated as a potential antidepressant, but the work was abandoned when it was found that the drug had stimulant properties similar to amphetamines. Now banned in many countries.

9. Countries That Have Taken Action

Austria: Announced 18 December 2008 that Spice would be banned.

Canada Health Canada is debating on the subject.

United States: A DEA ban will make JWH-018, JWH-073, JWH-200, CP-47,497 and cannabicyclohexanol, illegal when finally published in the Federal Register.

Source Information

Source information and quotes are from conversations, articles, interviews, and websites that are either currently ‘up’ or were published online in the last six months. They include:

John W. Huffman, Ph.D., Clemson University

Clemson University, Department of Chemistry webpage

Psychonaut Web Mapping Research Project

Katy Bergen, Columbia Missourian Newspaper

Jeanne Whalen, Wall Street Journal Online

The Pitch Action News Team, Kansas City

University of Freiburg, Baden-Wurttemberg, Germany

Wikipedia, online website

WebMD, online website

European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, Lisbon (EMCDDA). EMCDDA is a decentralized EU agency providing information for policymakers and professionals in the field.

Journal of Neuropsychiatry Online, Drs. Catherine Taber, Robin A Hurley

Ask.com Encyclopedia

CBS News.com

Top

«« First |

« Previous |

Records 51 to 58 of 58 |